Published on 27 April 2022

Replete with detail, yet with an almost gruesomely lifelike quality: it’s no doubt that the artificial hands and fingers that Mr Ambrose Lim crafts are a work of art.

Up close, every tiny crease in the skin is visible – even the faint blue-green tinge of the underlying veins. The disembodied limbs probably wouldn’t look out of place on a horror movie set or at a wax museum.

But his work isn’t in art per se; rather, Mr Lim is a prosthetist, specialising in artificial replacements of the upper limb.

“Some other prostheses that you might have seen are a little bit more plasticky, or they might look like they’re from a mannequin,” he explained. “Or there are the ones that look like machines – heavy-duty, sort of like the kind that Captain Hook uses.

“But here, we specialise in making lifelike silicone prostheses…it’s a more artistic, more customised kind of service.”

The field is niche enough that there are only two such prosthetists in Singapore, and both of them in the same team at the National University Hospital (NUH). In fact, as far as Mr Lim is aware, they’re the only ones within the region that can produce these prostheses, with patients coming from as far as the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Latvia, and Serbia.

In addition, the prosthetic technology they use is unique, developed by the NUH team itself.

“We have patients referred to us from other hospitals, or overseas, who come to us specially for our prostheses,” he said. “Everything is done in-house – nothing is outsourced.”

The art and science of prosthetics

Tucked away in a nondescript-looking corridor at NUH, the Prosthetic Hand Clinic is small, a bit cluttered, and – contrary to its name – utterly unclinical.

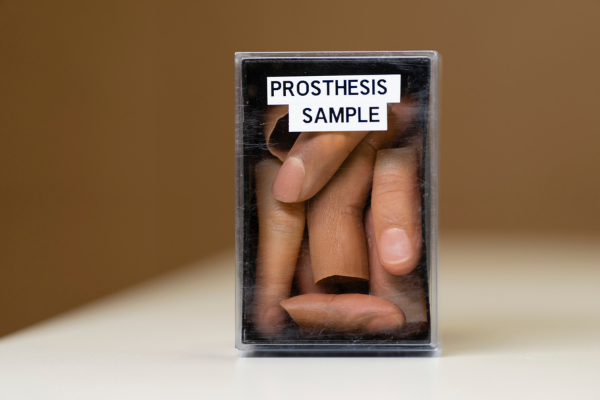

In fact, apart from a small consultation set-up at the front part of the room, it gives off the air of an art studio, or perhaps a workshop. A paintbrush and small pots of paints lie unattended on a workbench, with equipment hanging in an organised disarray from a tool rack on the wall. And inside a filing cabinet, boxes are crammed full of silicone fingers and hands of every shade and size.

This clinic has been Mr Lim’s workplace for the past seven years. However, he is still considered an apprentice under the mentorship of Chief Prosthetist Mr Michael Leow – in part because to become a full-fledged prosthetist, he needs a certain number of cases under his belt, including both finger and hand prostheses.

“Most of our cases involve finger amputations because of traumatic accidents,” he explained. “There are occasional cases involving congenital malformations and pathological conditions…but we don’t have that many cases [of more severe hand and forearm amputations].”

The second reason: the creation of realistic-looking prosthesis is a precise, time-consuming craft that involves more than mere artistry. With a single finger prosthesis taking about a week to make, it requires a close reproduction of the layered structure of the skin.

Getting the final product right is particularly important, as on average, a patient will use a single prosthesis for about five years.

“[So] you need to be very meticulous and perfectionist, every step of the way,” said Mr Lim. “From step one when you meet the patient, to making the impression moulds, and then to the painting of the nails and the skin…we work very closely with the patient to ensure that they’re happy with the product.”

This painting process is, in Mr Lim’s view, the most difficult part of the job. To mimic the multiple layers of our skin, different layers of pigments are mixed and then applied to the prosthesis – first the translucent dermis layer, and then the more opaque intramuscular layer.

Even with such careful attention to detail, not every patient walks away satisfied, said Mr Lim. “With our skin, the colouration comes from natural pigments such as melanin, carotene, and oxygenated blood,” he explained. “But in our prostheses, synthetic pigments are used instead. So the colour changes from lighting to lighting…and even if the colour is a match in one light, it may look quite different in another.”

There are also other small (but no less important) details to consider in the making of a prosthesis that can affect how natural the fit will be.

For instance, he had a patient who had three fingers amputated at the same time. One was successfully reattached – but the others were not.

During the patient’s visit, Mr Lim noticed that the reattached finger had lost some of its length during the procedure. “So we shortened the two prosthetic fingers as well, so it matched the overall length,” he said.

In addition, because of the trauma, the skin around the patient’s amputated fingers were a much deeper red shade than the rest of his body.

“So we also matched the traumatic colouration,” said Mr Lim. “These are some of the tricks we do to help the patient.”

A job with purpose

The prostheses that the pair in NUH create don’t serve an active function. They can’t be used for identification – for security reasons, the fingerprints are ground off. They do aid in passive hand function by providing an opposable post for the remaining digits to work against (for instance, when holding a mug or a phone), but they’re not meant to be working replacements.

Instead, the prostheses are much more important to a patient’s body image, which affects their emotional and psychosocial well-being, said Mr Lim.

This is especially true for patients who lose their limbs in traumatic accidents – often in workplace injuries, although traffic and domestic mishaps, such as fingers getting crushed by a slamming door, are sometimes involved. “I’ve even seen a patient, an elderly woman, whose hand got sliced off when she was cleaning a blender,” he recalled.

As such, many patients who come in are deeply affected by the accident, and often show signs of lingering trauma.

“You can see from their behaviour, when they take off their prosthesis during appointments – they will hide their hands, put it in their pockets, their bags,” he said. “Or they’ll wear a glove or bandage to cover it.”

In such cases, a prosthesis can help the patient to better cope with their injury and move on with their lives, Mr Ambrose said.

He recalls a patient who had the tip of her finger bitten off by a horse. “She was really traumatised…she was on the verge of tears when she first visited us,” he shared.

“We wanted to make it really nice for her, so we asked her to come back a few extra times so we could get it perfectly fitted for her. We could see throughout the process, she was getting more and more happy, more and more excited…and when she finally got it, she was smiling from ear to ear.”

As such, despite the challenge of the job – especially for such as Mr Lim, who comes from a non-artistic background – the work remains fulfilling, interesting, and different every day.

“It’s not like some lab work, where you do the same thing every day. Here, the process is more or less the same, but each patient and each case is actually very different,” he said.

“It’s nice to do something few others can do, and deliver a good product to [the patient] and see them really happy with the results…to make prostheses that will help them clear this chapter of their lives, accept their injury, and move on.”

Click here to find out more or to join us as a prosthetist.

In consultation with Mr Ambrose Lim, Senior Technician, Department of Hand and Reconstructive Microsurgery, NUH.